by lizzi | May 28, 2019 | Newsletter Vol. 6, Project Profiles

By Dorinda Dallmeyer The Altamaha is a river of superlatives. Formed by the confluence of the Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers, the Altamaha drains the third largest watershed on the eastern seaboard. With the Oconee’s headwaters stretching into the foothills of the Blue...

by lizzi | May 28, 2019 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 6

By Dorinda Dallmeyer Known for creating conservation solutions that “make environmental and economic sense,” The Conservation Fund is one of many partners collaborating on land conservation in the Altamaha watershed. Andrew Schock, the Fund’s Georgia State...

by lizzi | May 23, 2019 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 6

By Dorinda Dallmeyer If you want to experience the mighty Altamaha watershed firsthand, it’s now possible to paddle 443 miles on designated water trails from near the river’s headwaters east of Lithonia all the way to Darien. It’s not quite...

by lizzi | May 23, 2019 | Donor Profiles, Newsletter Vol. 6

By Dorinda Dallmeyer Cherishing coastal Georgia comes naturally to Dr. Marsha Certain. The daughter of a physician, she grew up in Brunswick. After graduating from the Medical College of Georgia and completing a cardiology fellowship at Emory, her love of coastal...

by lizzi | May 23, 2019 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 6

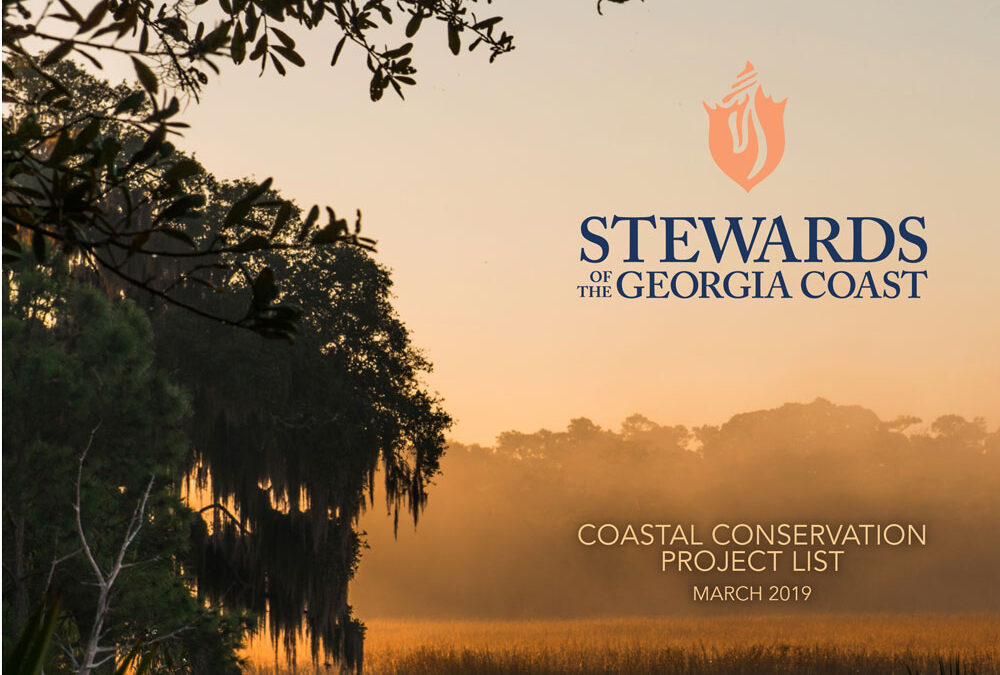

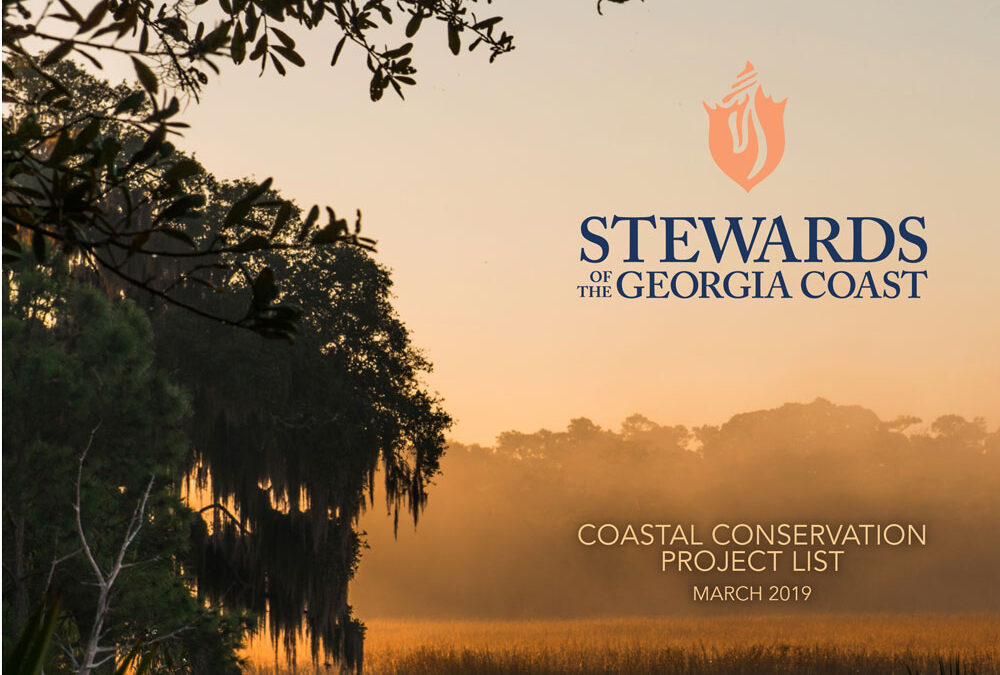

When meeting with people new to coastal conservation, we’re often asked, “How can we help?” To answer that question broadly and responsibly, Stewards has released the second edition of its Coastal Conservation Project List, a curated menu of high priority conservation...

by lizzi | May 23, 2019 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 6

($2,500 committed/$27,500 needed) In 2015, The Nature Conservancy acquired 4000 acres in the Altamaha watershed, strategically positioned where the river meets the salt marsh in Glynn County—the historic Altama tract. Today, the property is owned and managed by the...