By Dorinda Dallmeyer

The Altamaha is a river of superlatives. Formed by the confluence of the Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers, the Altamaha drains the third largest watershed on the eastern seaboard. With the Oconee’s headwaters stretching into the foothills of the Blue Ridge and the Ocmulgee’s into the heart of south Atlanta, the Altamaha drainage basin covers approximately 14,000 square miles, more than a quarter of the state. Because the Altamaha flows across the gently sloping Coastal Plain, it’s a poor candidate for dams. As a result, the Altamaha remains the longest free-flowing river system on the East Coast and also has the largest river discharge south of the Chesapeake Bay.

Photo by Jim Barger

The Altamaha is far more than the water it carries. From the confluence to the sea, its 137-mile long valley features a great diversity of habitats: forested swamps and bottomlands, shaded bluffs, old-growth longleaf pines, isolated sand ridges, freshwater wetlands which are succeeded in turn by tidal marshes and barrier islands. It hosts 234 species of rare plants and animals — some found nowhere else on earth. The Altamaha system is such a unique complex of habitats that the Nature Conservancy named it one of the “Last Great Places on Earth.”

The Nature Conservancy’s Christi Lambert has championed protection of the Altamaha for over 25 years. “Because the watershed is so large, many people who live upstream may not even realize they are part of it. But the health of the Georgia coast depends on land and water use practices all the way downstream. The Altamaha feeds us, connects us, inspires us, and humbles us. Despite all that has happened in the ecosystems making up the Altamaha watershed, the river reminds us of the power of resilience. We have an opportunity and the responsibility to care for it today and into the future.”

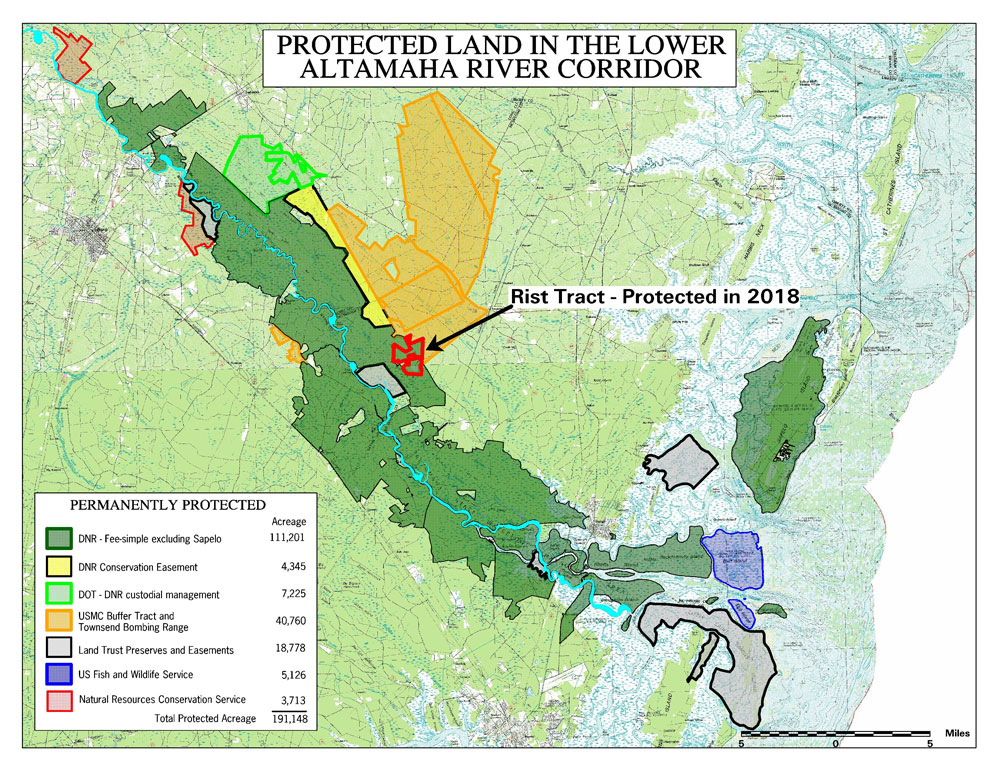

Recognizing the Altamaha’s unique attributes, federal and state agencies, non-profit conservation groups, businesses, industries, and private citizens have collaborated over decades to create a conservation corridor now protecting more than 180,000 acres on both sides of the river, from Jesup to the Atlantic. Private philanthropy has played a significant role in this work.

Jen Hilburn, the Altamaha Riverkeeper, has her own reasons for championing the Altamaha. “I was trained as an ornithologist. That work usually focused on one bird species or maybe a suite of species. Protecting the Altamaha at the ecosystem scale means we are not only conserving individual species but all the interconnections that make this river a hotspot for biodiversity. At the same time, I’m excited to see all the people enjoying the river, the families who are making memories for their children that will last a lifetime. Through conservation, we are protecting our communities, our heritage, and our future.”

Much of this protected land is managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Steve Friedman, DNR’s Chief of Real Estate, attributes this success to the watershed’s high conservation value. “Everything comes together in the Altamaha,” says Friedman. “This is a story of the power of collaboration among stakeholders. We have incredible biodiversity plus a place that is important to a lot of people. Also most of these areas are accessible for public recreation in all its forms. There is no way that we could have succeeded in protecting this corridor without partnerships and philanthropy.”

This burgeoning mosaic of public and private reserves not only is saving wild nature, it preserves Georgia’s cultural and ecological birthright for generations yet to come. Private landowners have been key in accelerating protection for the Altamaha. Newspaperman and Jesup native Dink Nesmith gave his own reason for protecting five miles of his family’s Altamaha River frontage and cypress forests under a conservation easement. “Foresters tell me that many of these trees predate the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World. A few may have been standing when Christ prayed in the Garden of Gethsemene. We are conserving and protecting a legacy for the great-great-great-grandchildren we will never know. If you won’t stand up for the people and places you love, who will?”

Top photo by Blake Gordon