by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 2

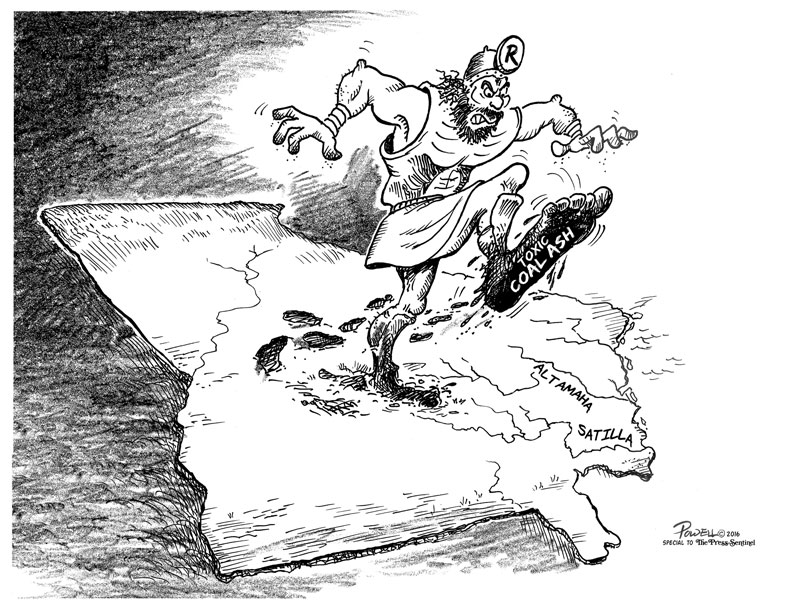

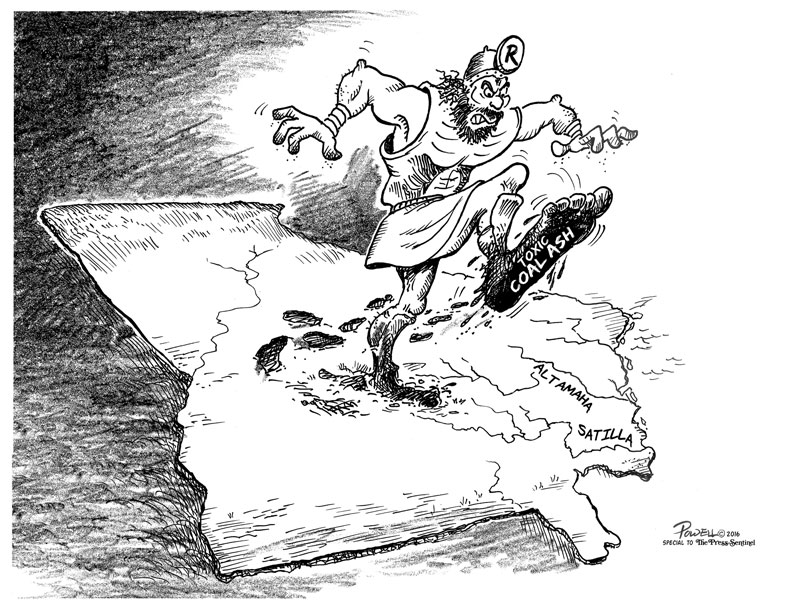

Coastal residents and conservation organizations are continuing to challenge plans for a Wayne County landfill to accept up to 10,000 tons of coal ash per day from neighboring states. This represents a more than 500% increase of their current daily intake of 1,800...

by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 2

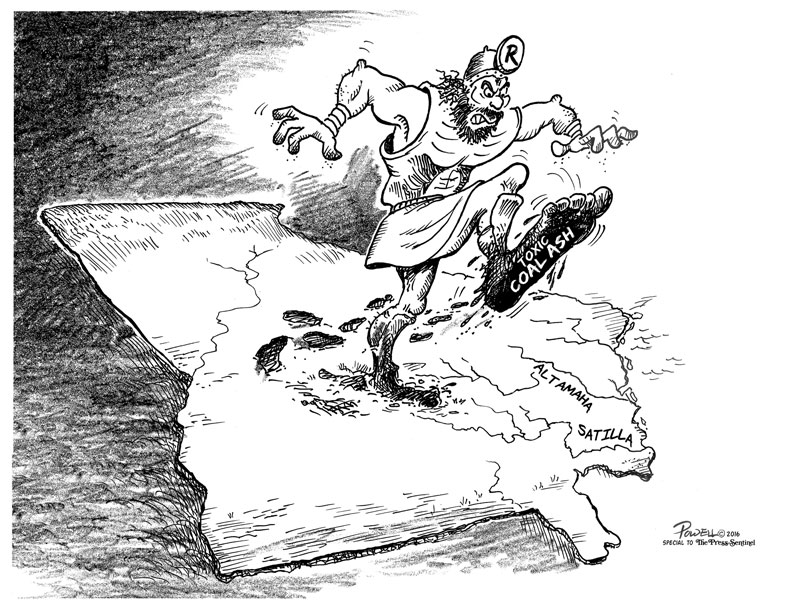

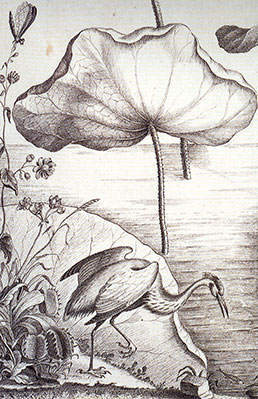

More than two centuries have passed since the publication of botanist William Bartram’s Travels in 1791. Bartram’s descriptions of his journey through the American South between 1773 and 1777 continue to ignite the imagination of those who love nature and the thrill...

by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | Donor Profiles, Newsletter Vol. 2

The Lamar Mixson Sea Turtle Internship is a celebration of love and a young man’s passion for wildlife and wild places. Lamar spent the summer of 2011 on St. Catherines Island as an intern for the island’s sea turtle conservation program. That summer of protecting...

by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | Donor Profiles, Newsletter Vol. 2

George Parsons, born in 1826 and raised in Maine, worked with his brother to build successful business ventures in southern cities, including Savannah. Parsons was known for his strong family ties, a concern for community needs, and generosity. Parsons established a...

by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | Newsletter Vol. 2, Project Profiles

During the 2016 Conservation Donors Roundtable, The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) announced the award of a $75,000 grant to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Non-Game Division (DNR) and several partners for monitoring, studying, and protecting...

by lizzi | Nov 15, 2016 | Newsletter Vol. 2, Project Profiles

An anonymous donor took major action this July with a $1 million challenge grant to the St. Simons Land Trust’s Campaign to Preserve Musgrove. “Now is the time to take care of this island,” he said, citing land conservation as a great way for folks to make a positive...