by lizzi | Jun 25, 2021 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 10

By Dorinda Dallmeyer We may give a name to an island but we are defined by the imprint it leaves on us. Humans have been part of the Ossabaw landscape for over 5,000 years. As they did on many other Georgia barrier islands, native peoples left behind evidence of their...

by lizzi | Jun 25, 2021 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 10

By Abby Sterling, Ph.D. Director of Manomet’s Georgia Bight Shorebird Conservation Initiative As you make your way to Ossabaw Island through winding tidal creeks, you pass shell rakes lining the marshes and sand bars and mudflats that are exposed at lower tides....

by lizzi | Jun 25, 2021 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 10

By Burch Barger From St. Simons to Brunswick to Townsend to Darien, Stewards have gathered this year in beautiful, conserved places along the Georgia coast to learn and explore together. Highlights of our four field trips, described below, included ideal weather,...

by lizzi | Jun 25, 2021 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 10

By Burch Barger As you may recall, Stewards and the Communities of Coastal Georgia Foundation successfully collaborated in 2017 to “crowdfund” the $10,000 purchase of a Kawasaki mule UTV and related equipment for Georgia DNR’s Wildlife Conservation Section to use on...

by lizzi | Jun 25, 2021 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 10

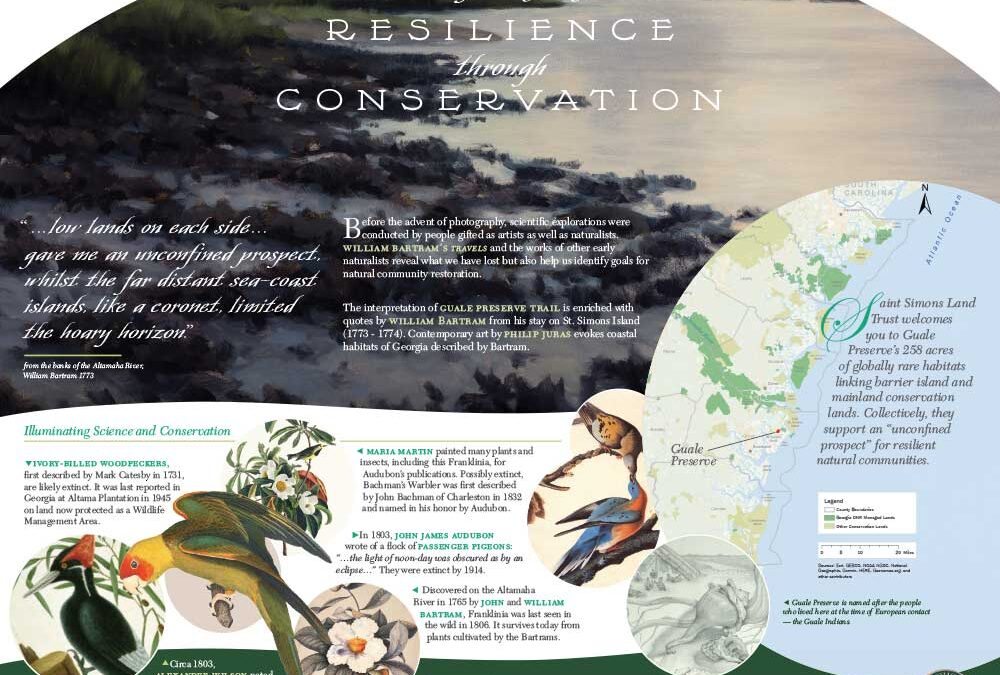

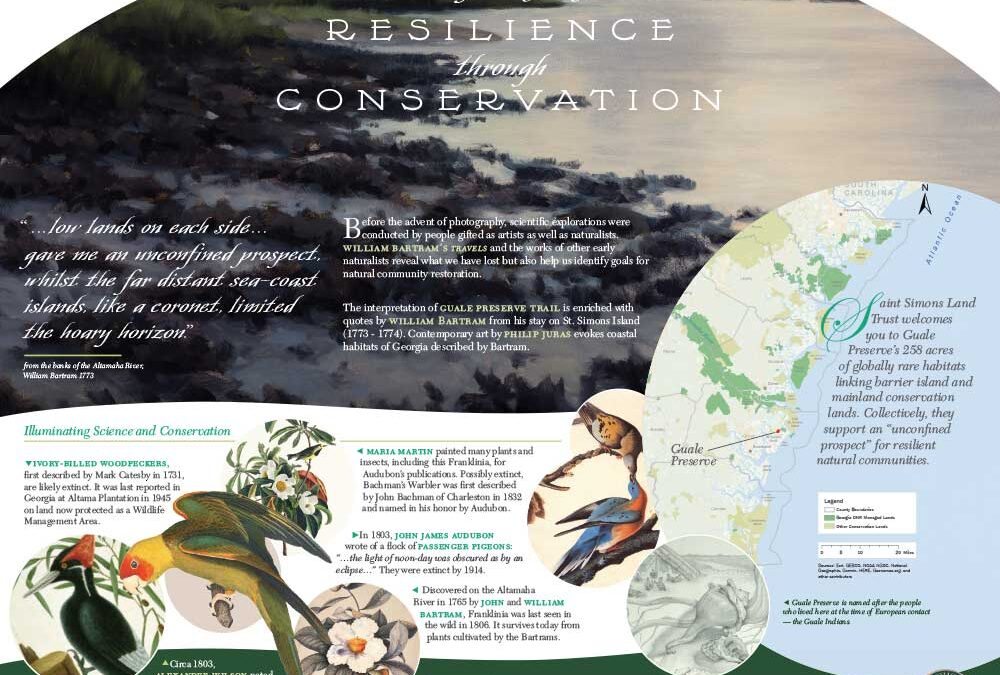

By Burch Barger On your next visit to St. Simons Land Trust’s Guale Preserve, be sure to check out the new interpretive signage posted along Polly’s Trail. Coastal naturalist Christa F. Hayes used observations from William Bartram’s 18th century explorations of the...

by lizzi | Dec 7, 2020 | News & Updates, Newsletter Vol. 9

By Dorinda Dallmeyer Fifty years ago, Georgians statewide fought hard to preserve our coastal landscape – a fight that centered just south of Tybee. There the coastal marshlands faced a novel, existential threat because of geology. During the 1960s, mining companies...