By Dorinda Dallmeyer

Fifty years ago, Georgians statewide fought hard to preserve our coastal landscape – a fight that centered just south of Tybee. There the coastal marshlands faced a novel, existential threat because of geology. During the 1960s, mining companies negotiated options to buy mineral rights on Little Tybee and Cabbage Islands. Their goal was to strip away the marsh sediments and extract extensive phosphate deposits that could be turned into fertilizer. The crisis intensified in early 1968 when the Kerr-McGee Corporation applied for a license from the Georgia Mineral Leasing Commission to mine phosphate from thousands of acres of the state-owned seabed offshore of Wassaw, Ossabaw, and St. Catherines Islands. Their plan called for dumping the mine waste atop neighboring barrier islands and marshland.

Kerr-McGee’s public relations campaign emphasized the putative economic benefits of the project. But the corporation failed to sway the Georgia public due to the efforts of a unique coalition of coastal scientists, students, conservation organizations, garden clubs, historical societies, hunting and fishing groups, and newspapers that rallied citizens statewide.

Remarkably, one figure in the fight was long deceased. Georgia poet Sidney Lanier (1842-1881) composed his famous work, “The Marshes of Glynn,” based on his observations of the marsh at Brunswick, Georgia from dawn to twilight. Combining descriptions of plants and animals of the marsh with the rhythms of the tidal cycle, the poem is deeply grounded in the spiritual impact Lanier felt before the majesty of God’s creation. Because generations of Georgia schoolchildren memorized the poem, people across the state were familiar with the coastal marshes even if they had never seen them for themselves. For them, mining Sidney Lanier’s marshes would be losing part of Georgia’s cultural heritage.

Others fought for the marshes based on their ecological value. The scientific studies of University of Georgia ecologist Eugene Odum and his colleagues at the Sapelo Island Marine Institute had established the importance of the coastal marsh functions, from primary productivity rivaling that of the rainforests to the marshland’s importance as a nursery grounds for fish and shellfish. To convey to the public that the marshlands were not just pestilential swamps, Odum borrowed a concept from the space race of the 1960s – the “life support system.” Just as astronauts could not survive in space without their life support systems, Dr. Odum argued that the marshes also provide a vast array of ecosystem goods and services vital to our life on Earth and to our coastal economies. To bring this message home, he and his graduate students barnstormed the state on an educational tour to explain the science behind why the marshes were more valuable in their natural state than destroyed for fertilizer production.

Another force supporting marsh protection were Georgia’s garden clubs. Mobilized by pioneer conservationist Jane Yarn, garden club members peppered the state legislature with thousands of letters opposing the destruction of Georgia’s coastal landscape. Newspapers across the state put mining the marshes on the front page and opposed it in their editorials. One editorial cartoon featured Sidney Lanier being scraped up by a bulldozer while penning the first lines of “The Marshes of Glynn.”

Representative Reid W. Harris guided the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act of 1970 to passage in the Georgia House and Senate

The full-throated public outcry from this massive coalition swayed the legislature and state agencies to not only deny Kerr-McGee’s license request but to move forward with comprehensive protection for Georgia’s salt marsh. The Coastal Marshlands Protection Act of 1970, based solidly on ecological science, placed the state in the role of trustee whose foremost duty is to serve the public interest in managing proposed activities in the marsh. In 1979, the state adopted the Shore Protection Act to control human activities within the sand-sharing system. It, too, was based on sound ecological and geological principles.

According to historian Chris Manganiello, the passage of these two acts represented the “gold standard” for environmental engagement. The fight to save the marshes created an organized environmental movement in Georgia which has multiplied and thrived in the intervening decades. The lessons learned fifty years ago continue to inspire a coastal conservation ethic that protects our natural heritage and seeks to meet the coming challenges of climate change impacts at our coast.

According to historian Chris Manganiello, the passage of these two acts represented the “gold standard” for environmental engagement. The fight to save the marshes created an organized environmental movement in Georgia which has multiplied and thrived in the intervening decades. The lessons learned fifty years ago continue to inspire a coastal conservation ethic that protects our natural heritage and seeks to meet the coming challenges of climate change impacts at our coast.

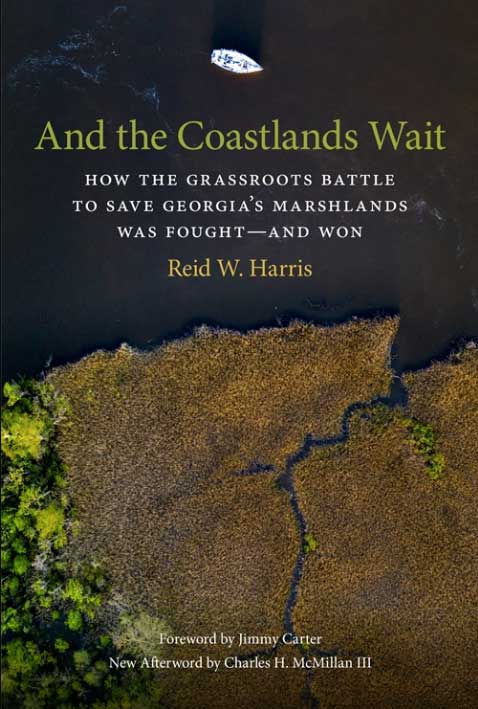

For a first person account of how the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act was pushed through the Georgia state legislature in 1970, we recommend Representative Reid Harris’s book, And the Coastlands Wait: How the Grassroots Battle to Save Georgia’s Marshlands Was Fought – and Won. It was republished this year by The University of Georgia Press with the philanthropic support of coastal conservation advocates.